Are we building earth science apps like video games?

When I watch satellite imagery render in a browser, I sometimes have a strange thought: the graphics chip doing this work is the same one that renders entire procedurally-generated universes in modern video games.

But it's not just the hardware. The operations themselves are strikingly similar, from GPU-accelerated reprojection to mesh-based rendering and transformations that warp massive worlds across your screen. Except in our case, we're warping Earth. One team is rendering alien planets, we're rendering the one we're actually standing on.

This convergence between Earth observation tools and game technology isn't exactly new. What's interesting isn't that it works, it's realising how steadily (slowly?) we're adopting the playbook from an entirely different industry.

Welcome to what I hope becomes a regular conversation about where Earth observation technology is heading. On a regular basis, I'll try to share thoughts on the strange and fascinating evolution of our field, not to announce breakthroughs, but to reflect on what the shifts actually mean. Let's start with how we got here.

The Grid Computing Days

Twenty years ago at ESA's ESRIN facility in Frascati, I was operating what we thought was cutting-edge: a grid computing system for processing satellite data, the kind of infrastructure that would eventually evolve into today's cloud platforms. We ran production lines that generated weekly Antarctica mosaics, monthly atmospheric maps, ocean colour measurements. Each one took hours, sometimes days.

The workflow was heavy, industrial. You could almost hear the servers grinding through the processing chains. Science teams would submit their algorithms, and we'd integrate them into workflows that transformed raw measurements into usable products. The whole thing felt too permanent, too heavyweight for what should have been iterative exploration.

Something Changed

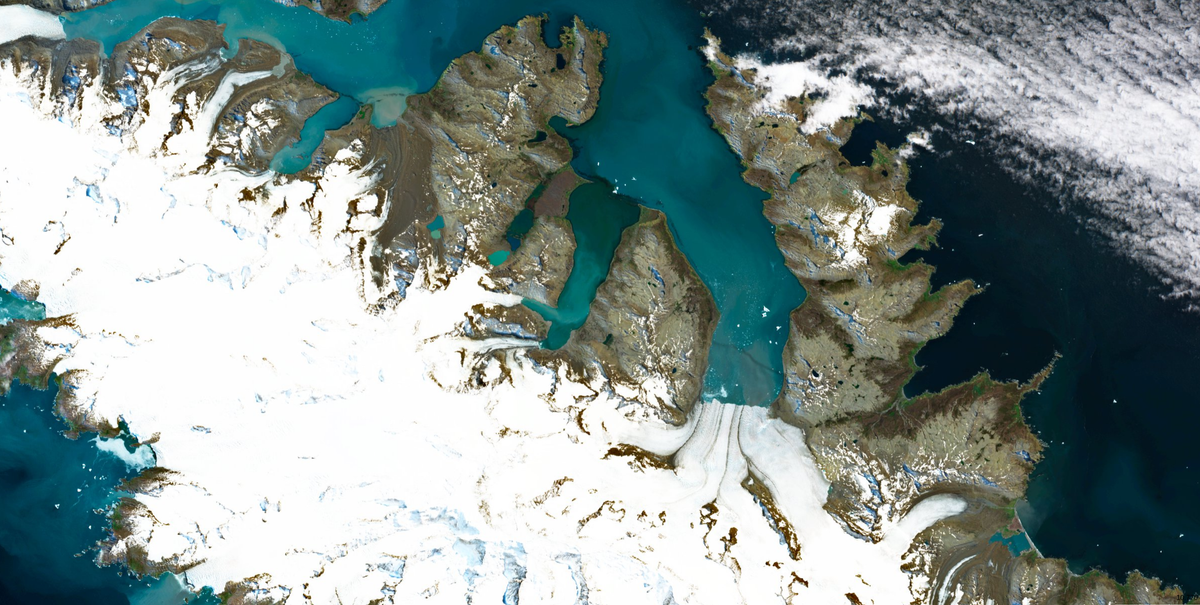

Fast forward to now, and that same data - sometimes the exact same type of measurements, just from newer and sharper remote sensors - renders in your browser. Immediately. You can adjust how spectral measurements are combined, switch between different ways of looking at the data, reproject it onto different map references. The graphics chip in your laptop is doing work that used to require dedicated processing clusters.

The technology isn't new; what's changed is that this has become the expected approach. When we built Sentinel Explorer project recently, nobody questioned whether a GPU-accelerated rendering library belonged in the browser. It was just the obvious choice. That quiet shift from "impressive demo" to "default architecture" is worth pausing on.

The Video Game Question

So here's a question: could we someday find satellite imagery or climate-derived products in a game engine's asset store? Right between particle effects and castle environment packs?

Don't be surprised if space agencies start posting openings for "Level Designer - Earth System" or "Post-production Manager - Climate Data Assets." It sounds like a joke, but the convergence is real enough that the punchline is fading.

The question isn't whether we'll literally adopt game engines for satellite data - it's that we're already solving the same problems with similar approaches. The techniques, the mental models, the architecture patterns are converging. And that convergence tells us something about where the whole technology stack is heading.

From Pre-Rendered to Procedural

Those production lines on GRID computing? We were essentially pre-rendering assets, the same way early video games shipped with hand-crafted levels baked onto the disc. Every weekly mosaic, every monthly product was a fixed output that users would download and use as-is.

Now we're doing something closer to what No Man's Sky does with its 18 quintillion planets. We don't store every possible combination of satellite bands or derived index. Instead, we store the raw measurements and the rules for combining them. Users generate their own view on demand, in real-time, tuned to exactly what they need to see.

The shift from "download pre-computed products" to "stream raw data and compute your own" mirrors the shift from "play our carefully designed levels" to "explore this procedurally generated universe." It's not just faster, it's a fundamentally different model of what a "product" even is. And increasingly, it's not even a choice: the sheer volume of data being produced by modern satellite constellations is making the old download-and-process model physically impractical. You can't download everything anymore. You have to stream.

And the parallels keep going. Over the past year, I've watched us build cloud-native storage systems that look suspiciously like video streaming platforms, with formats like Cloud Optimised GeoTIFFs and Zarr using compression and chunking strategies that optimise how data flows from storage to screen, the same way a streaming service optimises how video reaches your living room. The mental model has shifted. We're not building data processing pipelines anymore, we're building streaming systems with playback controls.

Where we've already converged

It's worth acknowledging just how many game engine concepts have found their way into our toolbox, whether by direct inspiration or independent convergence. Level of Detail, the idea that you render less detail when zoomed out and sharpen progressively as you zoom in, is exactly how multi-resolution tile pyramids work. Games only render what's inside the camera's view, ignoring everything off-screen; our cloud-native formats do the same thing with spatial indexing, fetching only the tiles in your current viewport. That experience of a map "sharpening" as you pan? It's literally the same texture streaming technique that games use to load assets progressively.

These shared concepts work so well that most people never notice them, which is precisely the point. Creating false-colour composites or calculating vegetation indices starts to feel more like applying Instagram filters than running scientific algorithms. The convergence at this level is already well advanced. The interesting question is what comes next.

Where we haven't converged yet

So here's what I find fascinating, because the game industry has spent decades solving problems that Earth observation is only beginning to face. We've reached similar solutions for rendering, yes. But some of their most powerful concepts haven't crossed over at all.

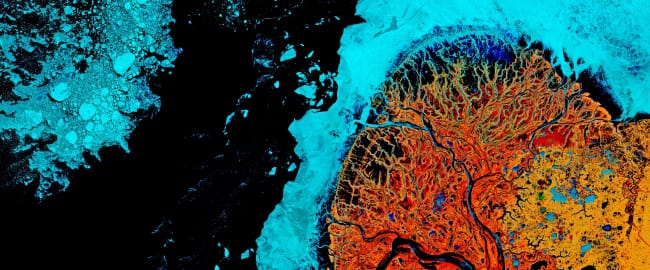

Real-time physics, not just visualisation. Every modern game has a physics engine running alongside its graphics. Objects fall, water flows, things collide, and crucially, the physics and the rendering are integrated. What you see is what the simulation computes, in real time. Now consider: when you look at a flood extent derived from radar imagery in a browser, you're looking at a snapshot. What if the viewer had an embedded physics engine? Not a simplistic game-style simulation, but one that integrates science-controlled algorithms, the kind of validated models that hydrologists and atmospheric scientists actually trust. You see where the water is from the latest satellite pass, and the system runs forward predictions using the terrain data already loaded in the scene, potentially even exploring multiple scenarios or ensemble runs to capture uncertainty.

This has another advantage that's easy to overlook. Satellites in low Earth orbit don't observe the same spot continuously, they pass over every few days at best. Between two passes, you're essentially blind. A physics engine fed by real observations could fill that gap, interpolating what's likely happening between acquisitions based on the last known state and the governing physical laws. The observation and the prediction become one continuous, fluid experience rather than a series of disconnected snapshots.

Atmospheric simulation. Modern games simulate how light physically bounces through a scene, scattering, reflecting, refracting through materials. In Earth observation, we have atmospheric correction models that do something conceptually similar, estimating how sunlight scattered through the atmosphere before reaching the sensor. But these models run offline, as slow batch processes, and their outputs are distributed as entirely separate product levels. What if we applied real-time ray tracing on the GPU to atmospheric correction, making physically accurate light simulation interactive rather than something you wait hours for? If the rendering engine itself can model atmospheric effects on the fly, you might eventually stop needing pre-computed corrected products altogether. You'd just need the raw top-of-atmosphere measurements and let the ray tracing engine do the rest, on demand, tuned to the exact conditions the user cares about. It's the same shift from pre-rendered to procedural, applied one level deeper.

Autonomous agents exploring data. In games, non-player characters have goals, react to their environment, and make decisions. This idea of autonomous agents operating within a complex environment hasn't really been applied to satellite data. Imagine deploying "agents" into your data cube, processes that patrol the data looking for anomalies, that react when they detect change, that can be given high-level goals like "monitor this coastline for erosion" and figure out for themselves which data to fetch, which calculations to run, and when to raise the alarm. We're starting to see this with AI assistants, but the game industry's decades of experience designing agent behaviour in complex, evolving worlds is something we should definitely look into for inspiration.

Narrative systems for decision-making. Perhaps the most unexpected parallel: games are extraordinarily good at guiding people through complex decision spaces without overwhelming them. Dialogue trees, branching narratives, systems that remember your choices and adapt the options ahead. Now think about city planners trying to understand flood risk. Instead of handing them a dashboard full of maps and numbers, what if the system guided them through a structured conversation? "You're concerned about flooding in this district. Here's your current exposure. Would you like to explore what happens under a 50-year scenario or a 100-year one?" Games have been refining this kind of guided exploration for decades, and it maps almost perfectly onto the challenge of turning Earth observation data into decisions.

Ready player one?

Now, none of this is entirely new thinking. Projects like NVIDIA's Earth-2 and the European Destination Earth initiative are already pushing towards digital twins of the planet, and research has started exploring the integration of geospatial data into game engines for applications (e.g. Rantanen et al., 2023). But when do they become something you can actually put in the hands of a decision-maker as a minimum viable product?

I believe we're still not quite in the gaming industry mindset. And to be clear, this isn't about making Earth science entertaining, even if that would be a welcome side effect for reaching a larger public. It's about making it more effective, especially when it comes to decision-making. The game industry hasn't just built beautiful worlds, it's built worlds where complex systems become intuitive, where you can explore scenarios, test assumptions, and understand cause and effect without needing a manual. That capacity to make complexity navigable is exactly what we want to achieve, except that in our case, the consequences are very real.

Who gets to play?

So far, most of the progress has lowered the barrier for people who were already close to the technology. And that's valuable, no question. But the urban planner evaluating flood defences, the farmer deciding when to irrigate, The demographer studying urban choices impacts, the insurance analyst pricing coastal risk, none of these people should need to understand rendering pipelines or data cube architectures. They need answers, scenarios, and guidance.

The risk is that we focus too much on the technological stack and not enough on what it enables. We're getting really good at making data renderable and manipulable. But the leap from beautiful visualisation to insights that drive actual decisions requires reaching well beyond the people who build the tools. Making data "playable" for those who can code is one thing. Making it useful for those who need to act, that's a different challenge entirely.

Press start to continue?

So we've got data that renders beautifully in browsers now. We're starting to glimpse what happens when the convergence extends beyond rendering tricks into the deeper architectural ideas from an industry that's been building immersive, interactive, intelligent worlds for decades.

When the barrier between "I have an idea" and "I can see the data" drops to nearly zero, what happens next? When physics engines meet satellite imagery, when agents patrol our data cubes, when decision-makers are guided through climate scenarios the way gamers navigate branching storylines, what does Earth observation become then?

Let's keep exploring those topics in future posts...

Follow Seeing Earth

New posts straight to your inbox.

Further Reading